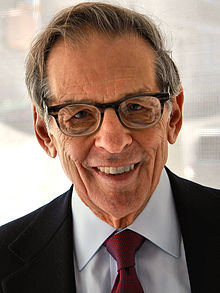

Robert Caro

Nieman Class of 1966

The bestselling biographer of Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson, Caro has won every major literary prize — some of them, such as the Pulitzer, twice. In 2010, President Obama awarded him the National Humanities Medal. This year, he won one of the J. Anthony Lukas distinguished-nonfiction prizes, given by the Nieman Foundation and Columbia University in honor of the late author and 1969 Nieman Fellow. Caro, whom the Times once described as “a man of Ahab-like writerly obsessions,” is legendary for both the meticulous research and the narrative skill evident in the two masterworks that have consumed most of his career: The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (which won the 1975 Pulitzer and was later named one of the hundred best nonfiction books of the 20th century), and the multi-volume Johnson biography, The Years of Lyndon Johnson. The first four of five planned Johnson books — The Path to Power, Means of Ascent, Master of the Senate and The Passage of Power — have been hailed as brilliant, essential reading on American politics, and as the “gold standard for presidential biographies.” Master of the Senate, which won the 2003 Pulitzer in General Nonfiction, has been called “a tale rife with drama and hypnotic in the telling” and “the most complete portrait of the Senate ever drawn.” The Economist wrote, “If Mr. Caro’s work on Johnson has not already set a new standard in American political biography, it surely will when his story of Johnson’s presidency is complete.” Caro has said that his work is less about “a man” than political power, the subject that has obsessed him for five decades. “Although the cliché says that power always corrupts,” he has said, “what is seldom said, but what is equally true, is that power always reveals.”

The bestselling biographer of Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson, Caro has won every major literary prize — some of them, such as the Pulitzer, twice. In 2010, President Obama awarded him the National Humanities Medal. This year, he won one of the J. Anthony Lukas distinguished-nonfiction prizes, given by the Nieman Foundation and Columbia University in honor of the late author and 1969 Nieman Fellow. Caro, whom the Times once described as “a man of Ahab-like writerly obsessions,” is legendary for both the meticulous research and the narrative skill evident in the two masterworks that have consumed most of his career: The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (which won the 1975 Pulitzer and was later named one of the hundred best nonfiction books of the 20th century), and the multi-volume Johnson biography, The Years of Lyndon Johnson. The first four of five planned Johnson books — The Path to Power, Means of Ascent, Master of the Senate and The Passage of Power — have been hailed as brilliant, essential reading on American politics, and as the “gold standard for presidential biographies.” Master of the Senate, which won the 2003 Pulitzer in General Nonfiction, has been called “a tale rife with drama and hypnotic in the telling” and “the most complete portrait of the Senate ever drawn.” The Economist wrote, “If Mr. Caro’s work on Johnson has not already set a new standard in American political biography, it surely will when his story of Johnson’s presidency is complete.” Caro has said that his work is less about “a man” than political power, the subject that has obsessed him for five decades. “Although the cliché says that power always corrupts,” he has said, “what is seldom said, but what is equally true, is that power always reveals.”

Recommended:

—The Power Broker. Excerpt:

In the beginning—and for decades of his career—the power Robert Moses amassed was the servant of his dreams, amassed for their sake, so that his gigantic city-shaping visions could become reality. But power is not an instrument that its possessor can use with impunity. It is a drug that creates in the user a need for larger and larger dosages. And Moses was a user. At first, for a decade or more after his first sip of real power in 1924, he continued to seek it only for the sake of his dreams. But little by little there came a change. Slowly but inexorably, he began to seek power for its own sake. More and more, the criterion by which Moses selected which city-shaping public works would be built came to be not the needs of the city’s people, but the increment of power a project could give him. Increasingly, the projects became not ends but means—the means of obtaining more and more power.

As the idealism faded and disappeared, its handmaidens drifted away. The principles of the Good Government reform movement which Moses had once espoused became principles to be ignored. The brilliance that had invented a civil service system was applied to the task of circumventing civil service requirements. The insistence on truth and logic was replaced by a sophistry that twisted every fact to conclusions not merely preconceived but preconceived decades earlier.

Robert Moses was America’s greatest builder. He was the shaper of the greatest city in the New World.

But what did he build? What was the shape into which he pounded the city?

To build his highways, Moses threw out of their homes 250,000 persons—more people than lived in Albany or Chattanooga, or in Spokane, Tacoma, Duluth, Akron, Baton Rouge, Mobile, Nashville or Sacramento. He tore out the hearts of a score of neighborhoods, communities the size of small cities themselves, communities that had been lively, friendly places to live, the vital parts of the city that made New York a home to its people.

—The LBJ books. The opening of Master of the Senate:

The chamber of the United States Senate was a long, cavernous space — over a hundred feet long. From its upper portion, from the galleries for citizens and journalists which rimmed it, it seemed even longer than it was, in part because it was so gloomy and dim — so dim in 1949, when lights had not yet been added for television and the only illumination came from the ceiling almost forty feet above the floor, that its far end faded away in shadows — and in part because it was so pallid and bare. Its drab tan damask walls, divided into panels by tall columns and pilasters and by seven sets of double doors, were unrelieved by even a single touch of color — no painting, no mural — or, seemingly, by any other ornament. Above those walls, in the galleries, were rows of seats as utilitarian as those of a theater and covered in a dingy gray, and the features of the twenty white marble busts of the country’s first twenty vice presidents, set into niches above the galleries, were shadowy and blurred. The marble of the pilasters and columns was a dull reddish gray in the gloom. The only spots of brightness in the Chamber were the few tangled red and white stripes on the flag that hung limply from a pole on the presiding officer’s dais, and the reflection of the ceiling lights on the tops of the ninety-six mahogany desks arranged in four long half circles around the well below the dais. From the galleries the low red-gray marble dais was plain and unimposing, apparently without decoration. The desks themselves, small and spindly, seemed more like schoolchildren’s desks than the desks of senators of the United States, mightiest of republics.

—Caro’s Davidson College lecture on his work. “Why do I think political power is so important?” he said. “Well for one thing, we live in America. Basically, at the end political power comes from … our votes. So therefore the more we know about political power the better informed our votes should be, and theoretically therefore the better our country should be.” Watch it here:

—“The Big Book,” Chris Jones’ Esquire profile of Caro. Excerpt:

When he is done for the night and turns off his ancient bronze lamp, Caro walks home, fifteen minutes, the same walk he makes every day, past Dino’s Shoe Repair, where his autographed picture hangs on the wall, and through Columbus Circle, to the apartment he and Ina have shared since 1972 or so. (He can’t remember exactly.) The apartment, near the top of an old gray stone co-op building on Central Park West, is expansive by today’s standards, grand and formal, paneled with dark wood. There are many shelves lined with many books, and they open, like doors, to reveal more shelves with more books. There are also photographs. One, black-and-white, is a photo taken of Robert and Ina on the night they met. She was just sixteen; he was nineteen, a young student at Princeton. He is wearing a tuxedo, no glasses yet, his thick hair cut short; she’s wearing a pretty dress. They are standing close to each other, smiling — his smile is wide; hers is shy. They had talked about books that night. “He wants his books to last because he had studied those books that had lasted,” Ina says. They have been together since.

She is a writer, too — her fixation is France — and she has been the only research assistant Caro has ever had. In her high school yearbook, which she pulls off the shelf, she painted her dream life under her portrait: “research worker.” She has lived her dream life: She has labored over boxes of documents, tracked down sources, made countless phone calls to places like Highland Beach to find men like Vernon Whiteside. She was her husband’s emissary when they traveled into the Texas Hill Country, trying to sift Johnson’s childhood out of the dust and the old women who lived there and remembered him as the man who brought them electric light. She even sold that pretty little house in Roslyn, unannounced, when they could no longer afford it, after Caro had spent so many moneyless years on The Power Broker, long having burned through his small advance. With their young son, they moved to an apartment in the Bronx. “We were broke,” Caro says. “It was a horrible, horrible time.” That’s when he worked out of the library, when his key to the Allen Room, a shelter for homeless writers, “was my most prized possession.” He can remember how much their rent was exactly, $362.73, because it was a figure that filled him with fear.

This is the last installment of our Featured Fellow series highlighting some of the Niemans who have distinguished themselves in narrative journalism and other artful storytelling. The series honors the history and legacy of the Nieman Foundation, founded 75 years ago this month. For the full series on Nieman storytellers, go here.