Our latest Notable Narrative is Tim Rohan’s New York Times story on Jeff Bauman, the Boston Marathon bombing survivor made famous by the photo of him being rushed to safety in a wheelchair, both legs lost. In “Beyond the Finish Line” Rohan parlayed exclusive access into an intimate account of the early stages of Bauman’s recovery. The story, accompanied by stirring Josh Haner photos and video, hits all the narrative markers: a strong character, scene, a compelling story arc, dialogue and detail, with careful attention to structure (six scenes/sections, 4,200 words) and point of view. The voice: elegant, restrained, nothing saccharine. Remarkably, Rohan is 23. A recent University of Michigan graduate, he was just coming off a Times internship and working as a stringer, covering his first marathon, when the story broke. Our Q-and-A with him follows, but first an excerpt of “Beyond the Finish Line,” from a scene with Bauman and his girlfriend, Erin Hurley:

One night, just as his patience waned, Hurley arrived; seeing her was the best part of his day now. They had been together for about a year. He had decided he wanted to marry her, buy a house with her, start a new life with her. But he sensed her guilt. She said she loved him more now. She was more affectionate. They had figured out how to be intimate in his hospital bed. She just had to be careful of his legs.

Now she kissed him and sat in the large chair next to his bed. He was lying there, his left hand behind his head. She was playing with her hair, twirling an end with her finger. She asked about his day. He wanted to talk about hers instead. She asked if she should renew the lease on her apartment. He hesitated. He tried to dissuade her, but when she resisted and made a case to keep the apartment, he suggested they buy a house together.

“It’s a lot of work buying a house, you know,” she said, looking down. She felt his eyes watching her. “You have to like — I don’t know. It’s a lot of work. It might be too much for you right now. And me, too.”

Rohan (pronounced ROW-an) lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and talked to us Saturday by phone. Here’s part of the conversation, edited lightly for clarity and length:

Rohan (pronounced ROW-an) lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and talked to us Saturday by phone. Here’s part of the conversation, edited lightly for clarity and length:

Storyboard: This piece wasn’t your first on Jeff Bauman. The day after the bombing you wrote the deadline story “In Grisly Image, a Father Sees His Son,” about Bauman’s father learning via the published photo that his son had been injured. How did that story come about?

Rohan: I was at the marathon to cover it as an event. I was about to file a feature when the bombs went off. Later that night after my sidebar was filed our assignment was to find someone to write about. By then I guess the New York Times had descended on Boston. There were a dozen or so, probably more, Times reporters up there. I went to Brigham and Women’s Hospital and I stood outside in the horde of media members for about three hours. There were these SWAT-looking police officers keeping everyone at bay. No one really wanted to talk. At about 10:30 at night they had a press conference and told us all to go home. On my way back to the hotel I thought, What the hey, I’ll stop at another hospital, see if I can find someone to write about. On a whim I decided to go to Boston Medical. So I stopped at Boston Medical and there wasn’t a horde of media, only a few stragglers. And, actually, funny story — ran into my college editor there (Andrew Grossman), who writes for the Wall Street Journal. He was outside. At Boston Medical I run into Jeff’s half-brother and his stepsister. I get their information. It’s almost 11 at night by now so there’s no way to get anything into the paper the next day; I’m just trying to make contacts. The next day I went back to Boston Medical. It had been such a whirlwind I didn’t even know anything about the picture; I didn’t know who Jeff was. I had just run into his family at the hospital the night before and they’d said, “My brother lost both his legs in the marathon.” So I went back and waited —

With a story about the brother in mind?

With anything in mind. I didn’t know who I was gonna meet. I didn’t know if any story was possible. I just had this one lead. One lead. I went back to Boston Medical and I just waited. I got there at 10 a.m. I waited until — the father’s side of the family finally came down for lunch at about 3 o’clock. I stopped them and explained who I was and that I had met the half-brother and stepsister the night before. We had a half-hour conversation and I ran to the local Starbucks and filed 800 words an hour and a half later. There was a lot of reaction to that story. After that, my editors had the idea to maybe do something bigger. We didn’t know what it would become but we knew we wanted to follow this guy and see what happened next.

There must’ve been a tremendous clamoring from other journalists to get intimate access to Bauman and to do the kind of story that you ended up doing. How did you do it?

I hung around Boston and stayed in touch with the father the rest of that week. My job from then on was to see what would become of the story. As I stayed in touch with father that week, Jeff was going through three surgeries — he was barely even seeing relatives. He wasn’t gonna meet with anyone. But less than a week later his father brought me up to meet him. I had been talking to the father about what we wanted to do, saying we just wanted to kind of detail Jeff’s comeback. So that first time I met him, he signed off on it. Once he moved on to Spaulding and he was more with it and his surgeries were behind him and the pain was a little less than it was at first, I think he decided to stick with me just because of that first story. And we kind of had a rapport from the start. He’s 27 but we’re kind of — we think the same, so we kind of hit it off. But that first story did a lot to build trust with him.

How much time did you spend with him, and over what period?

Where the timeline picks up in the story is where we started — two weeks after the bombing. So that Monday was the first day I really shadowed him. I got there at 8 a.m. and left at 6 that night. It kind of went that way for about four weeks. It wasn’t every single day but it was three, four days a week, sometimes five. After the first week and a half our photographer, Josh Haner, joined in, and he fit like a glove. Everyone loves Josh, so when he came in he made the atmosphere lighthearted. It was a good mix of people. That really was important, to keep Jeff at ease. So probably about the first week of June is when I pulled out a little bit and kind of came to the conclusion that we needed to write. By then Jeff had taken his first steps. By then we were working on the video and putting together the presentation.

How long did the writing take?

On and off, I guess going through notes, from when I started to the finished product, three weeks. And that’s, you know, a lot of rewriting. My college English teacher John Rubadeau always said the secret to writing is rewriting. So I rewrote sections, paid a lot of attention to word choice, pacing. A lot of thought and time was put into it. You know, there’s so many themes — it was difficult for me at first because I was so close to it and I’d been with him for two months by then, so figuring out which details were necessary took a lot of thought. There was a lot of reading sentences out loud and a lot of pacing, and having my friends read it and calling them late at night.

Writer friends?

I sent it to my mother. I sent it to my college editor at Michigan. I sent it to a buddy who’s still in Michigan. I sent it to colleagues. Just to get other people’s eyes on it. There was only so many times I could look of it. Someone would suggest something and I’d say, “Oh I didn’t think about it that way.” I was calling my one friend* at 2 in the morning discussing word choice with him, over the difference between “yanking” and “pulling.” At one point the doctor said, in the first section, “We’ll yank and cut,” and I was worrying so much about whether I should later use the word yank when in reality it was more like pulling. I was so worried about every little thing like that. And my friend made the point that I just needed to calm down. I was going insane. It was fun, though. When I look back on it and all the nice things people are saying about it, I had three months to report and write the story — I would’ve been upset if I hadn’t turned out the way I wanted it to. I wrote it as well as I could. It’s a peaceful feeling, that it’s done and I put the necessary time into it.

The piece begins with the scene where the doctors remove the sutures. What other scenes did you observe and discard, and why was it important to start with this one?

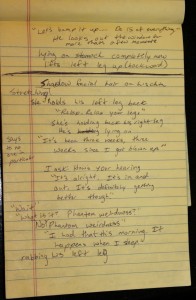

A page from one of Rohan’s notebooks.

I guess there were three things my editors and I agreed were important. You get in the top of section that this is his attitude — he’s wary and uneasy about this whole thing, and he’s taking things slowly, and it’s hard. I think it was important to get up high how painful this was. He was really an easygoing guy and he kept a lot to himself; he didn’t show a lot of pain and wasn’t crying himself to sleep. He really had a great spirit. This was the one moment in front of us, with Josh and I there, that he had this emotional outburst. And it was just so clear — I mean I went through all my notes but it was already so apparent which scenes needed to be included: It was the scenes that caused emotion in you when you were there, observing them. Like when the girlfriend’s saying, “I don’t think we’re ready to move in together,” or when James Taylor’s sitting there talking to him like a father would. The scenes that make you feel something. The final goal with that first section was to set up the struggle with him walking again. That was the central point on which the story revolves. Kind of setting up that after this, all that’s left to do is walk. These are his legs for the rest of his life.

The details are so good – Bauman could see an American flag at half-staff; he cried out on the third suture. Can you talk a little about reporting for detail?

I was just writing down everything, anything I thought was important. There wasn’t really a science to it. I made sure to count — when he cried out I double checked with the resident which suture she had done. I had noticed the flag outside and I saw him looking at it. By then, that was like two weeks into us hanging out, and by then I had been watching him for a while. When you spend that much time with someone you get to understand them a little bit better, so that made it easier to crawl into his head for those few moments. And it became easier to pick out what was important. I was just writing down as much as I could. I had five or six notebooks full that I had to go back through. When you figure out which scenes that build toward the end, you fill out the details that are necessary.

Do you also use a tape recorder?

Yeah. And I was writing down quotes, but it helped a lot that we were videotaping everything. Josh, amazingly talented photographer, was videotaping and shooting stills all the time. So while I was writing I was going back in the middle of the writing process and double checking, triple checking, the video. We had a videotape of the suture scene, and I believe we videotaped Jeff’s girlfriend, Erin, sitting down and talking to him; we had videotape of James Taylor. That made it 100 times easier. I wrote it all down and I wrote it down as I felt it, which helped me interpret the video. But it was like a database, right there, for me to go back and use.

It had to have been traumatic for Bauman to remember the details of the bombing. How did you approach it?

I probably could have done it better. I just kind of slipped in questions — I only did like two or three formal sit-down interviews with him and those were the ones we used for the video. Throughout those four or five weeks it was just me and him, and later on Josh, and we’d be talking about the Red Sox and I’d slip in a question — you know, “Do you think about that day?” or “Do you think about the bombers?” or “Do you think about your legs?” It’d be a question a friend might ask or his cousin might ask, or his mother might ask. Or I’d be there while he’s discussing these things with his mother. That was the great thing — everybody was asking the same questions. So I’d just be there and he’d be repeating himself to 20 different people. I was just there, for all of it.

You mention his friend Michele Mahoney being unable to move because “her left leg would not budge.” Was she badly injured?

This was one of those details that didn’t make it into the story but her room was next to his at Spaulding. I struggled with what to include, what not to include — what does the reader need to know about Michele Mahoney in order to know Jeff’s story? And all they needed to know was that her left leg wouldn’t budge. She in herself is a whole other story. So I was (mindful) to use details that added to the major point of the story. Pacing was important. I thought short, quick sentences would help you through some of it and keep the adrenaline going, maybe slow it down for the hospital scene but not too much.

This story never veers into melodrama or involves Bauman’s feelings toward the event itself, or toward the bombers, who are never mentioned by name. There’s no evidence of anger, except in the passage, “They expected him to be broken, angry and sad.” How did you decide not to go there?

He didn’t mention it. Bringing that stuff in would’ve been me adding it in. I thought the whole thing just had to be him as I saw him — sitting with him for those four or five weeks. Hanging out with him as he went home, as he went to therapy, everything — all the details, that was just what I saw, with context from the reporting. He just he didn’t talk about it, you know? I mean his mention of the bombers in the meeting with Dr. Carter and the other victims, that’s kind of where it came up. It would’ve just been me forcing it if I’d veered into that.

And the tone? How did you avoid melodrama?

What I kept thinking of — I don’t know if this is the textbook English-major answer — and I was not an English major — but I read a lot of Hemingway. And I could completely be misquoting him but I read somewhere about The Old Man and the Sea and how everyone thought it was this tremendous novel — it’s one of my favorite novels and I read it a lot while I was writing this story — but Hemingway said something along the lines of, “I wrote a story about this old man going out to catch this fish. Everything you see beyond it or whatever you take from it as a reader, that’s your own thing.” Every person reads the story differently and takes from it what they want to take from it. So he just told a story about an old man and the sea; and this was a story about Jeff trying to walk again. If I told that as plainly as I could, without long dramatic sentences or superfluous words or anything like that, if I could make the reader understand it as I saw it, they’d interpret for themselves what they need to know. I think about that a lot. Going back to the point about the bombers — did Jeff talk about them? No. So it doesn’t deserve words in the story. Thinking about the weight of words — you only have 4,200, so the amount of words you devote to something is important. So I guess that’s why it read so plainly, just because it was how I experienced those four weeks. If the reader can see exactly what I saw then they’re gonna experience the same feelings that I experienced when I saw Jeff walk for the first time.

Were you aware that this was a narrative? Did you set out with that construct in mind?

That’s my problem. That’s the only way I write. So I’ll turn a Tuesday Yankee’s game into some kind of epic novella. So that’s part of my fault right now — that was the joke about that first story, with his father. But it’s the only way I know how to write.

You never had to do daily inverted-pyramid stories?

I’ve never taken a journalism class. I’ve been to journalism camp. I worked at my college newspaper. I learned by doing and by experimenting, so inverted pyramid? I couldn’t tell you what that is.

Seriously? That’s hilarious.

No. I’m sorry. I’m just — I’m gonna keep experimenting, you know? We’ll see where my next opportunity comes.

What do you want to do?

I want to do this. I want to write long form. I want to write narratives for the Times, for a magazine, for anyone. I love it. Storytelling. Storytelling. And this was a heck of a story to tell. And there’s only so many places where you can still do great long-form journalism. I’m very aware of that. I’m 23 years old and I’m a freelancer for the New York Times and I know how lucky I am. There are so few of those places that still do these kinds of stories, and I’m at one of them; there’s only a few places where you can just go away for a few months and report and they put a photographer on it. Josh made the story a million times better just with his insight and his eye for detail — there’s details I would miss and Josh would mention them. We’d have long talks at the end of the day and go through our notes, or go through his pictures. We were so immersed in this story, it made the whole thing so easy and fun to do. It was so rewarding when it came out. It was made the way we wanted it to be made. It was something we could be proud of.

As a freelancer time is money, so if you take three months out to report a story, that means you’re not working on other stories that could pay the rent. So to ask the crass question, how does that work? Does the final payout adequately cover those three months?

It does. And I had money saved. And I may have had to borrow some money from my mother. But no, you know, the final paycheck covers those three months. That’s the life of a freelancer. Like I said, I’m in a good spot. The money was obviously important but I thought it was more important to spend that time making the story into something I was proud of. I could’ve seen Jeff two days a week and freelanced stories three days a week, or I could’ve done something completely different, but I wanted to pour myself into this. Josh was pouring himself into it. We wanted to make it something really great.

Some of the exposition falls naturally into the narrative — I’m thinking of the dialogue in the ambulance between a paramedic and Bauman. How old are you? Where are you from? Did you struggle with how and where to unpack the other exposition?

Him working at Costco kind of came up organically — it kind of came to a head when he’s sitting there looking at these new legs and the assistant was like, “What’d you do for work before this?” “Costco.” And then James Taylor asks, “Are you gonna go back to Costco?” It organically came up. The reader didn’t have to know about that until they had to know about that. That came up when Jeff was looking toward the future. He reaches this low point at the hospital and then you see him start to crawl out of it. He goes home, he goes to his buddy’s bachelor party, and then he goes to the prosthetist for the first time, and there’s kind of some hope. Like, “Look Jeffy, an all-amputee hockey team.” And then he goes to the Red Sox game and he’s this hero and then the James Taylor concert — the point isn’t that he and his girlfriend got the chance to go see a rehearsal, something no everyday person would be able to do; the point was the exchange that he and James Taylor had, where he’s being asked the same questions he’s kind of been asking himself but now it’s starting to get real because he’s gonna be walking soon. The trajectory of him lying in a hospital bed to taking those first steps — it just made sense because it was more relevant later stuff, to unpack the Costco stuff or the ear stuff.

Section 3 is when we meet his girlfriend. How painful that she kisses him goodbye and goes for a run. I like that you don’t explore the psychology of that, for her or for him. Sounds like you only dealt with issues that came up organically.

Yeah, but I asked about it. I didn’t ignore it. I asked him the questions I needed to ask him, but the organic stuff made the narrative, and it was just how he felt. It was important to stick to the point.

That’s part of the strength of this story, what’s not there. Narrative relies on specific detail but sometimes the abstract stroke is stronger. For instance, in the scene just after rehab, when he climbs back into bed and watches television — it’s just “television,” not the specific show or shows. It’s perfectly neutral.

Yeah, the details that matter. Would it matter if he was watching SportsCenter versus cartoons? Maybe it would’ve given a little peek into him but what does that matter, what he was watching in one particular instance of his day over a course of six weeks?

Did you write every day or wait until you’d done all the reporting?

I waited, because I didn’t know when the story was gonna end. Josh was getting a little anxious about — he wanted me to start writing. But there was really no deadline. I had an idea that once Jeff walked again that it would be time to write. I probably should’ve been writing the whole time; that probably would’ve made those last three weeks a lot easier. But no, he walked again and we were like, “Well okay, it’s time.” I had been transcribing along the way. Once I had everything transcribed and all the videos to go through and all the notes to go through, it was just picking things out and writing and trying.

Great kicker. How did you arrive at that?

I wanted to end with him walking again. We could’ve just said he took five steps, right? But to me it was important to show they were cautious — he took a big first step but they got more cautious after that. “Big” being a relative term. The whole thing is just — he’s cautiously going through everything: his relationship with his girlfriend, his hearing, his legs, his family, everything; walking again. It’s uncharted territory. And it really stood out when I watched the video of him over and over again, taking those steps. I thought it was a nice way to encapsulate the whole thing.

What was the biggest challenge to reporting this story?

The biggest challenge was getting Jeff to trust us. Everyone dreams of having that access to someone. And like I say, it was easy once we got in and we were all on the same page. We clicked, Jeff, Josh and I, and the family, and that made it easy to just kind of be around. I mean the first week was awkward. We were getting to know each other. Just imagine going through physical therapy having already gone through what he’d been through, and having a reporter sitting there with a notebook for eight or 12 hours a day. I had to bide my time. I didn’t ask so many questions at first and was just trying to hang out and get to know him, and let him get to know me. It’s just being a human. Knowing when to back off, when to let him rest, when to ask a question. It was kind of this dance we were doing, and by the end, it was so easy.

You’re a Times freelancer. Tell us a bit about your journalistic background and what led you to this story.

I went to the University of Michigan and I was originally an engineering major. My mother was an engineering major. My freshman year at Michigan my father passed away. He had Parkinson’s, so it had been a long kind of thing. When I went to Michigan I was trying to decide between journalism — sportswriting in particular — or engineering. My mother wanted me to be an engineer; then my father passed away and I kind of decided I’d go head first into this thing and do what I love. So I spent all my time at the student newspaper — covered the women’s basketball team, the hockey team, the football team for two years. Every summer I did an internship at the Erie Times News, and at the Cape Cod Times I covered the baseball league for the summer. After my junior year I worked at the Philadelphia Inquirer. It’s so easy when you know what you want to do and you just put your head down and go for it. Each summer, just talking to people and sourcing and reading and writing — reading helped the most. I made a big jump, in my opinion, junior to senior year of college, just because I took the time to read for two hours a day. I was reading newspaper stories that I liked, and novels. Then after my senior year I had a summer internship with the New York Times. So I get to the New York Times and the first week of orientation — that Friday, I volunteered to cover a Mets game, and Johan Santana ends up throwing a no-hitter while I’m there. So first week on the job I’m covering a no-hitter. These are the kind of things — you can’t practice that. You can’t practice how to write on deadline. You can’t, like, prepare for it; you just have to do it. So that was invaluable experience. At the end of the summer our tremendous college football writer ended up leaving to go to Sports Illustrated and they asked me to stick around. They extended my internship through the fall. So I stuck around and did some college football stuff. I guess the internship technically ended sometime in December but I stuck around and filled in wherever they needed me. I’d pitch stories just like any other writer. So I’m filling in on odd stories, and I just so happened to be assigned to the Boston Marathon on April 15. I’d never covered a marathon before.

What are the prospects for full-time employment at the Times? Is that something you’d want?

Yeah, I want to work there full time, but there’s only so many spots. Of course I’d love to work there full time, but it’s not like it’s that easy. A lot of people would love to work for the New York Times. I’m in a position where I may not be on staff but I can write a narrative like the one I just wrote. I have the attitude that if I keep improving, keep writing narratives that I think are quality, and if I keep getting better at it, someone will let me keep doing it. It was more important to me to write that (Jeff Bauman) story as well as I could than to worry about where my next paycheck was coming from. People ask me, “Why don’t you go write for this publication or that?” I love the people at the New York Times. They’re incredible. So many talented people. So we’ll see what happens.

*The friends who fielded the late-night phone calls were Nick Spar, Rohan’s managing editor at the Michigan Daily, and Zach Helfand, a sportswriter and writing Michigan senior. “It was with Zach that I had the 2 a.m. discussions over yanking vs. pulling,” Rohan says. “He stopped answering my calls toward the end of the writing. I thank those guys all the time, and they’re too modest to say it but talking stuff over with them helped a lot.”